Florida panthers are not considered immune to an emerging deadly genetic condition in new research led by UCF

picture:

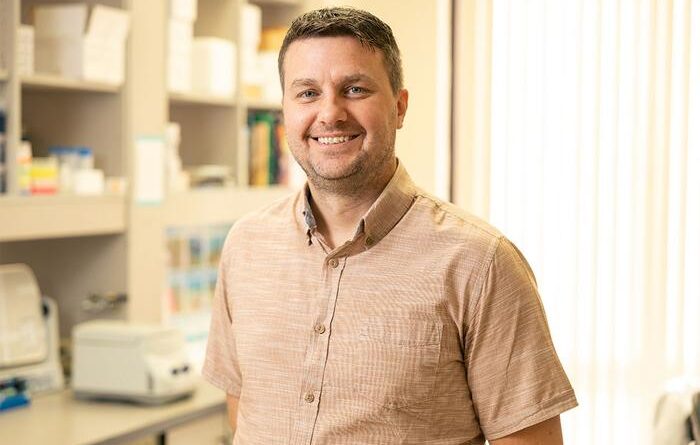

Bob Fitak, a UCF assistant professor of biology, collaborated with student researchers under his mentorship with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission to monitor Florida’s population for potentially fatal diseases. .

sight Again

Credit: Photo by Antoine Hart

Researchers at the University of Central Florida have helped with a study that found Florida panthers are less susceptible to an infectious disease that causes cognitive decline that leads to death in their prey.

The findings ease concerns that the deadly disease, known as chronic wasting disease, threatens the species.

The study, published this week at Journal of Wildlife Diseasesmeans Florida panthers are not at increased risk of contracting the disease. Chronic wasting disease is caused by a misfolded protein known as a prion and can be transmitted through contact between animals and prey, such as a panther that eats a deer with the disease.

UCF biologists were collaborating with partners at other universities and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) to monitor genetic changes as part of a broader conservation effort, when they examined This specific disease after chronic disease was found in Florida-white-tailed deer. in 2023.

Pumas — the common name for panthers in western North America — were introduced to Florida from Texas in the 1990s to help restore a dwindling population, says Bob Fitak, an assistant professor of UCF biologist and co-author of the study.

About 30 years ago, there were only 20 or 30 panthers left in Florida, and [became] it’s really born,” Fitak says. “So, they brought panthers from Texas to help supplement this population, to help restore or restore the population. It was a very successful program. We are trying to understand why that worked and what we should pay attention to in the future. We call this gene rescue or gene restoration.”

According to the FWC, there are approximately 120-230 panthers in the nation. Although the introduction of the same species means more genes and new concerns, the study provides further evidence that this is the right net, Fitak says.

“We’re not modifying the Florida panthers in any way to make them susceptible to disease,” he says. their risk here in Florida may be different than the rest of the country.”

A devastating disease has spread across North America in elk and deer, and conservationists worry it could infect predators that eat elk or deer as prey. Any creature that eats deer can be at risk, so it’s important to keep an eye on these people, says Fitak.

He says: “We sequenced the DNA of this gene in a group of Florida panthers, and we were able to show that Florida panthers are less susceptible to attack than other species of pumas in North America. It’s a good thing. We know in other countries pumas can eat infected deer and not get sick. So, we think the same thing will happen here in Florida, and we don’t see the danger growing Florida panthers to this disease.”

Fitak credits FWC and the study’s lead author, Elizabeth Sharkey, a student who participated in UCF’s 2022 Undergraduate Research Experience program under her mentorship, for making significant contributions to the research.

“We started with 37 Florida panther samples and four polymorphic sites, but when we started including more samples from Central America and South America, we found more diversity,” says Sharkey, who is now a graduate student in biological anthropology at the University of Washington. St. Louis. “I had the opportunity to do a lot of lab work to analyze the prion allele, and after my program ended, I continued to work with the team to write our manuscript.”

His early exposure to research through the REU program yielded positive results.

“Our research has uncovered a new Central American prion allele that was likely introduced into the Florida panther population before the famous genetic rescue in 1995 when five Texas pumas were killed,” says Sharkey. brought to Florida. “When this investigation began, prion disease had not yet reached Florida, but on June 30, 2023, the FWC identified the first case of a deer with prion disease in Florida.”

He continued to research and collaborated with Fitak and others to analyze DNA samples and eventually found that Florida panthers are not vulnerable.

“It was a big relief that our research provided evidence that panthers would be healthy and less susceptible to attack because of the introduced alleles,” says Sharkey. “Fortunately for the Florida panthers, the new allele does not appear to be responsible for prion disease, and is rare or absent in the current population of Florida.”

Fitak says he is encouraged by the findings reported in the study, and that he hopes the Florida panther population remains strong if chronic wasting disease spreads to Florida’s deer herd.

“Florida panthers might be fine if this disease spreads in Florida, hopefully it doesn’t,” he says. “The FWC in Florida is doing a good job of trying to limit the spread and monitor it.”

Information for Researchers:

Fitak is an assistant professor in the UCF Department of Biology in the College of Science. He received his doctorate in genetics from the University of Arizona and his undergraduate degree in genetics from Ohio State University. Before joining UCF in 2019, he worked as a postdoctoral researcher at the Center for Population Genetics in Vienna, Austria, and at Duke University. He is a member of UCF’s Genomics and Bioinformatics research group.

Sharkey is a graduate student in biology at Washington University in St. Louis. Louis and is part of the university’s Living Primate Lab. He earned a bachelor’s degree in zoology from Oregon State University and participated in UCF’s REU summer program in 2022.

Journal

Journal of Wildlife Diseases

Article Title

Prion Gene Sequencing in Florida Panthers (Puma concolor coryi) suggests no susceptibility to Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy.

Publication Date of Articles

20-Nov-2024

Description: AAAS and EurekAlert! are not responsible for the accuracy of the content presented on EurekAlert! by participating in organizations or for the use of any information through the EurekAlert system.

#Florida #panthers #considered #immune #emerging #deadly #genetic #condition #research #led #UCF